abstract

Nature can be integral to a city’s continued development and growth. However, the conventional physical growth of cities has led to an increase in the number of housing complexes displacing the natural environment. This continuing suburban sprawl disrupts habitat connectivity and results in a heavily-fragmented landscape, full of isolated habitat islands of existing natural reserves. When these reserves become isolated in this way, species movement across their boundaries declines.

The corresponding thrust of conservation efforts to mitigate this impact of suburbanization focuses on preserving untouched ecosystems, restoring degraded habitats, and maintaining existing parks and open spaces. And while this approach is useful, there is an urgent need for new examples of residential design that include the ‘weave’ of green landscapes that connect fragmented eco-systems.

As a testing ground for this idea, I have chosen a Seattle site that is in need of revitalization. Since Seattle is expecting employment growth and has set a goal to increase housing in the city to ease suburban sprawl, this exploration of new housing models could not be more timely. The project site is near an existing large natural habitat and has the potential to be connected to other natural-habitat areas in the city by corridor (strips of unbroken natural habitats) or by stepping-stone corridors (small patches of natural habitats).

On this site, I have designed a medium-density housing community to meet four goals. (1) Integrate natural habitat with human habitat and reconnect people to nature. (2) Revitalize the natural habitat within the urban context to enhance species population and diversity. (3) Foster a peaceful, relaxing residential community. (4) Give residents the sense of having their own space, with a safe, outdoor environment.

proposal

Humans need nature

The idea of biophilia, “the innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms,” suggests that not only do people like nature, but they want to be in and around it; it is hereditary and part of our nature (Beatley, 2011). For thousands of years, humans were hunter-gatherers, whose knowledge of, and relationship with the natural environment was crucial to their survival. Our brains were developed to need nature. True urban dwellers have only been around for a few generations, which is much too short a time to rewire the brain (Beatley, 2011).

Why can’t we live in the city, which is inherently sustainable due to the close proximity of everything, and have access to nature too?

Nature can be integral to a city’s continued development and growth. Not only do people have a need to be near nature, but the city needs nature to succeed in the future. Atkins in partnership with The Department for International Development and University College London authored Future Proofing Cities, which studies how cities need to work with the environment, instead of against it, in order to survive future climate change effects. With the removal of flood lands, agriculture, and forests for city scape, cities have set themselves up for natural disasters as they greatly contribute to climate change (Atkins, 2012). This central premise lead me to sustainable urban design, as I addressed: ecology, habitat loss and the island effect, habitat networks, natural ecosystems, urban developments, and biophilia. This project aims to achieve three goals: (1) Design a high density sustainable urban housing community. (2) Rehabilitate natural ecosystems in the urban context through habitat connectivity networks. (3) Integrate natural and human habitats to increases green surfaces for residential areas.

Focusing on the lowrise residential scale, I explored design strategies for sustainable buildings and their sites; the myriad systems they include. My aim is to design and develop a building and site plan that fosters a sustainable urban community by bringing nature into the built environment, mimicking natural systems in urban living, and becoming a stepping stone habitat connecting the surround natural habitats.

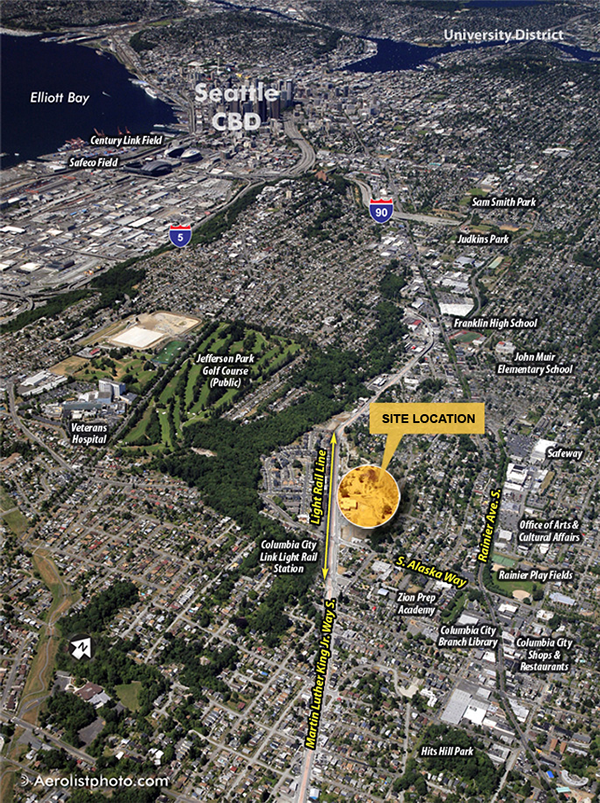

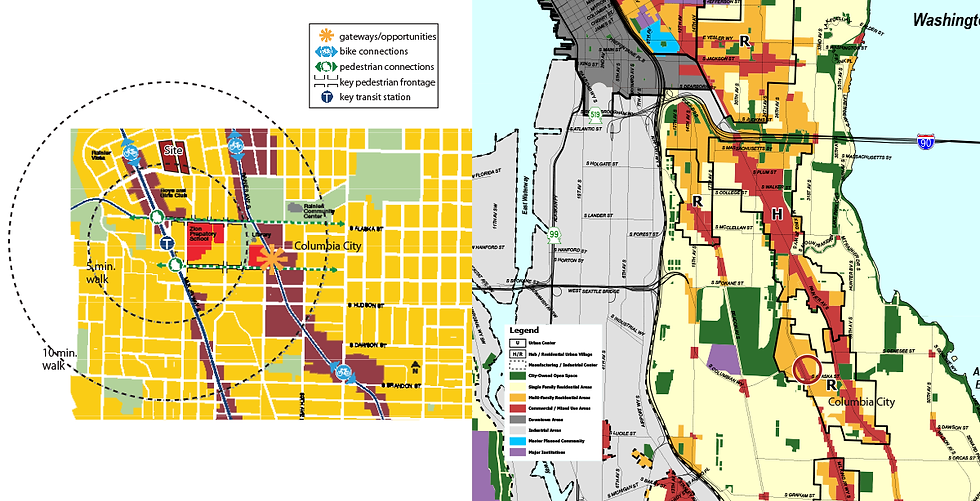

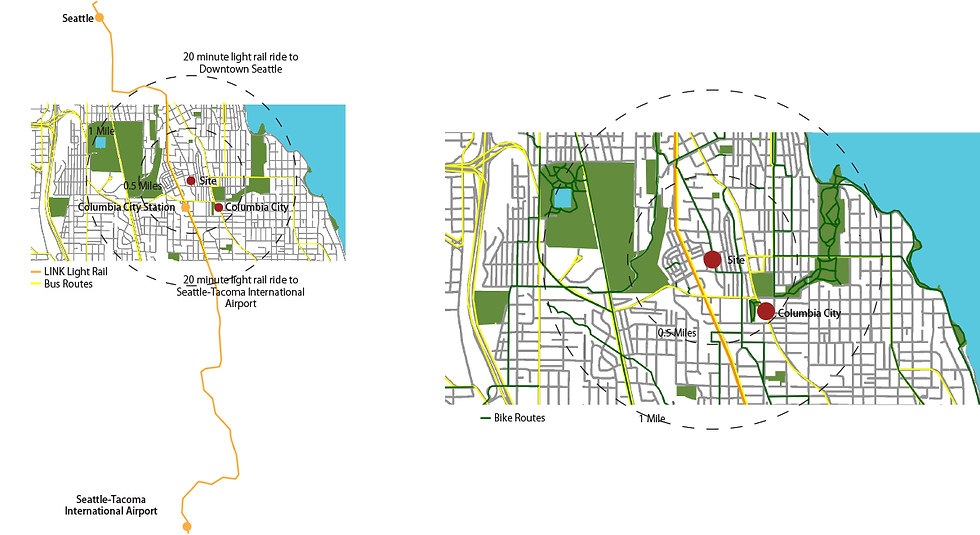

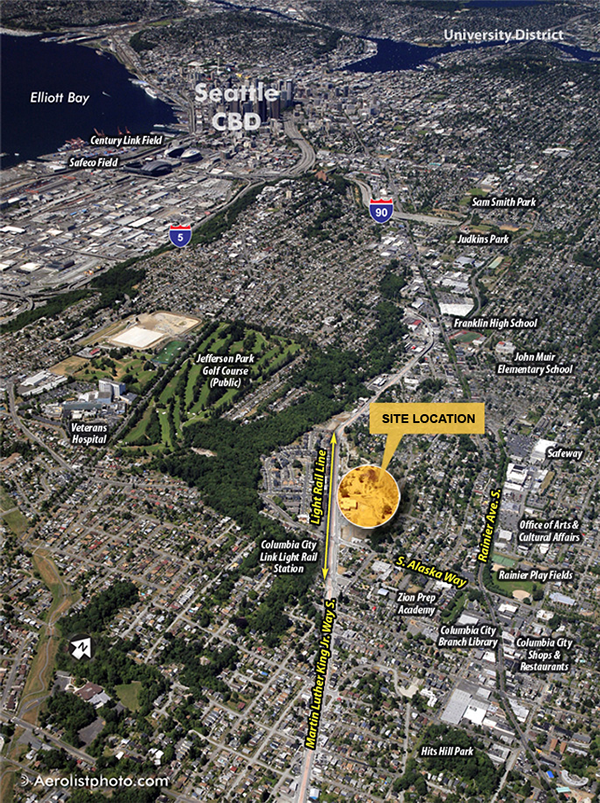

Public transit in Seattle includes streetcars, light rail, commuter train, ferries, local bus, and regional bus services. Columbia City is located at a transit hub where the light rail, local buses, and bike trails meet. This has been a coordinated effort to make the community more walkable and less car dependent. Columbia City is a mixed-used neighborhood, a complete community. Here residents are able to work, live, play, and reach commercial and retail needs by walking or short bus rides.

This site in Seattle was chosen due to its proximity to both the Columbia City residential urban center and close connection to downtown Seattle and the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport via the LINK light rail system. It was also chosen because of its adjacency to large habitat and parkland areas to allow the site to become a stepping stone habitat for wildlife traveling through.

site + context

The project site is located in the Columbia City neighborhood of Seattle, WA. It was previously low-density public housing, but was completely cleared in the early 2000s. The site was left barren until very recently when new higher density housing was built. The project is still unfinished, leaving east end of the neighborhood empty. This is where my project site is located.

Part of the new community is a mixed-use development with a few shops, a restaurant, and a convenience store. There are also several community services. The Neighborhood House Center offers services for low-income residents including classrooms, a Head Start program, computer lab, social and job services, and case management. Providence Health & Services provides services for seniors and people with special needs. The area’s Boys & Girls Club has a brand new 40,000 square foot facility and includes a Teen Center, gym, computer lab, classrooms, game rooms, multi-purpose areas, a music studio, kitchen, art studio, and health room. The neighborhood also embraces public art through murals, whirligigs on Columbia Way, custom park benches, and sculptures (Seattle Housing Authority, 2012).

final project

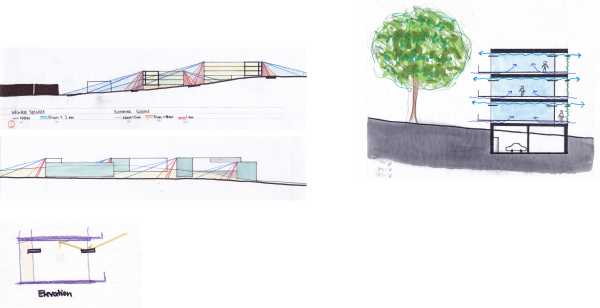

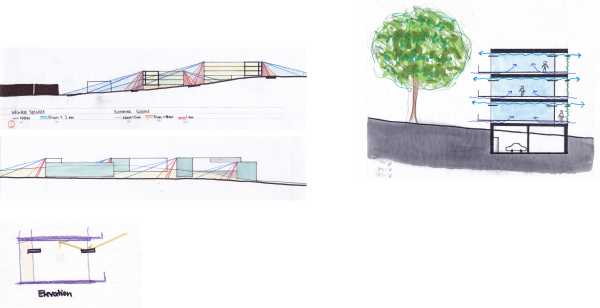

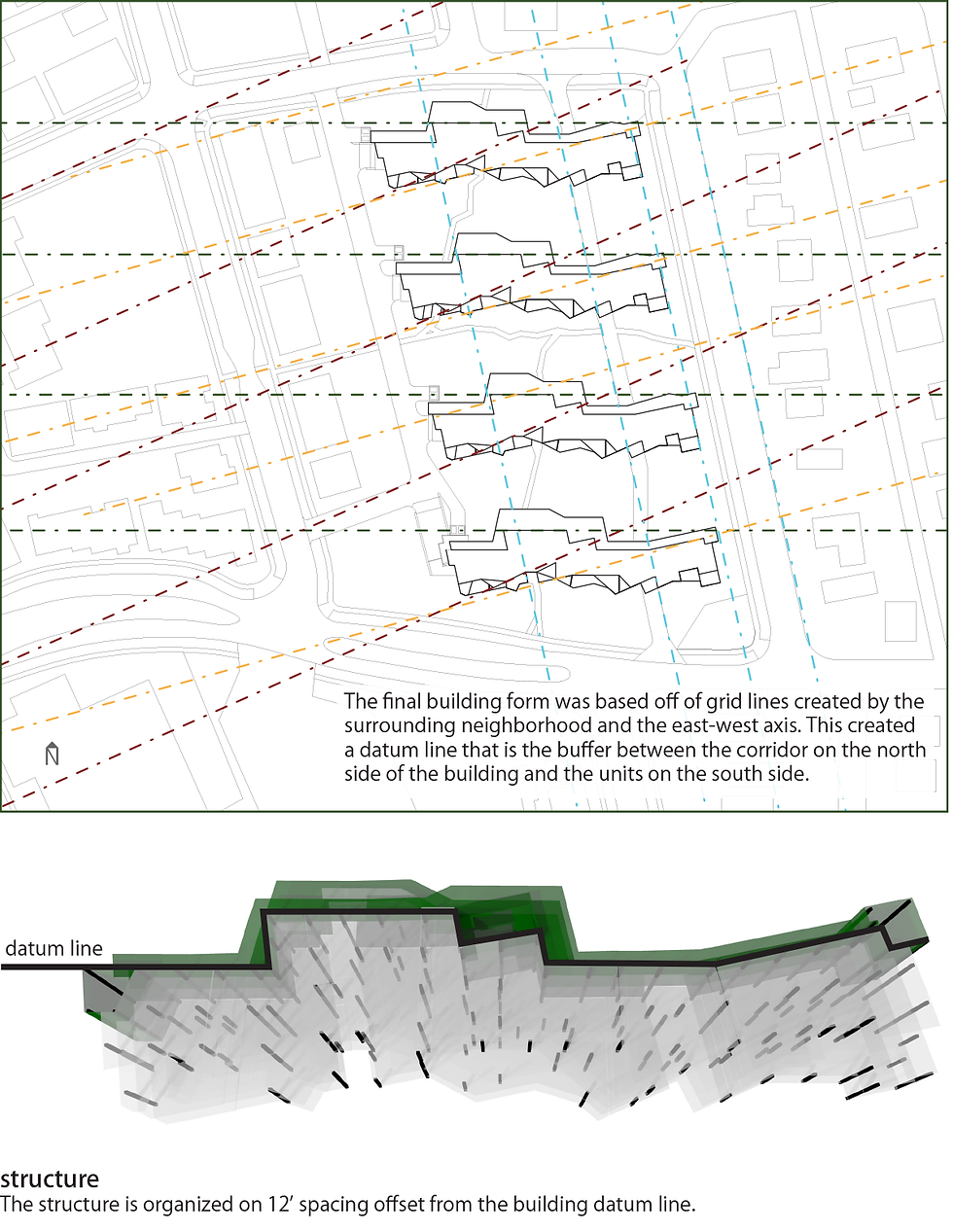

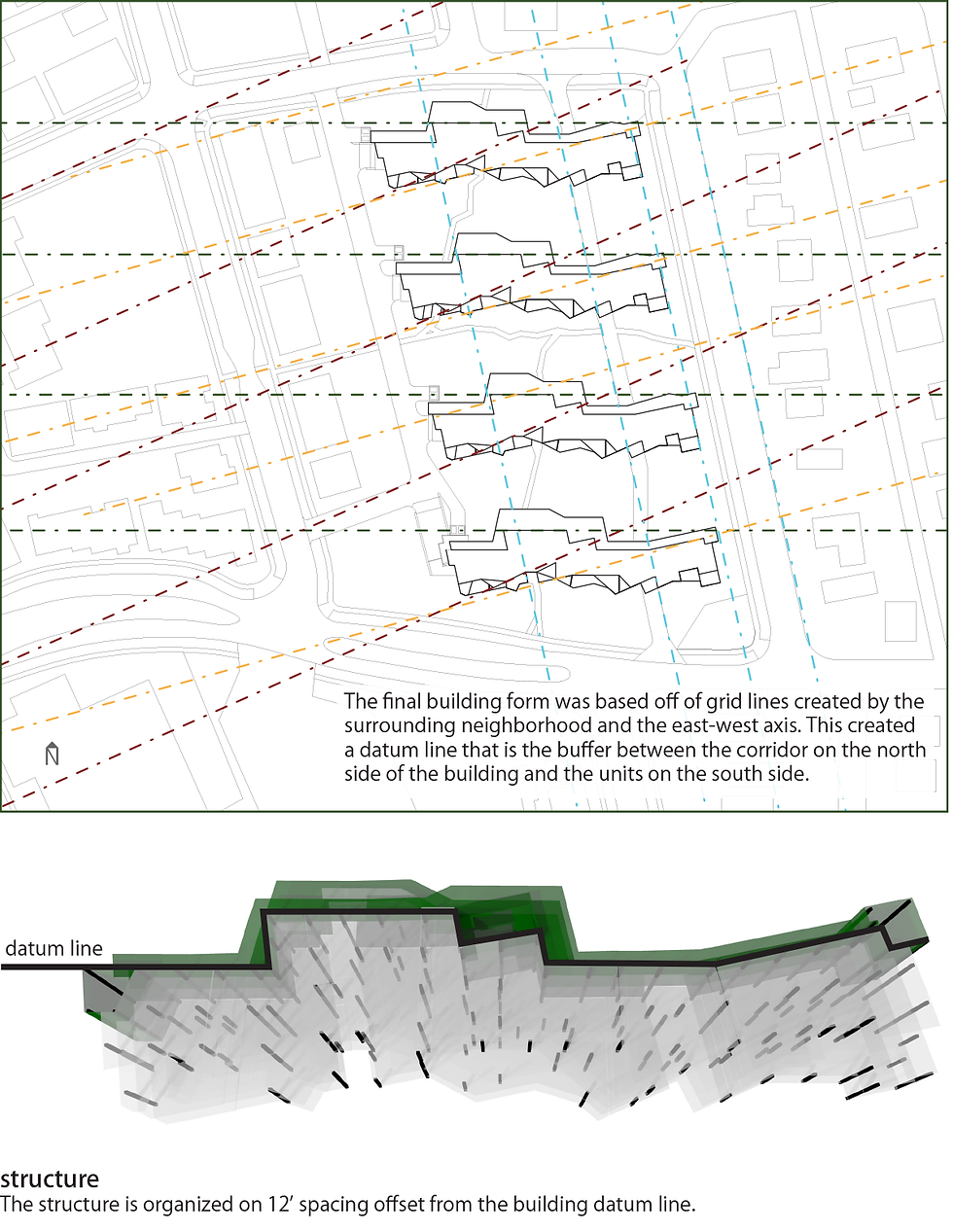

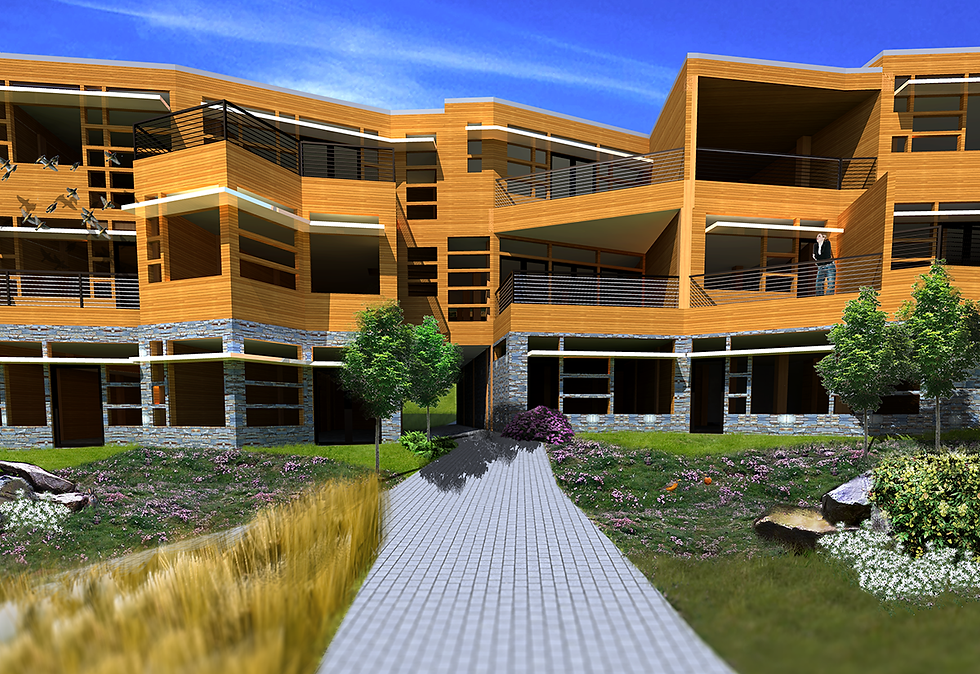

To demonstrate my thesis: “nature can be integral to a city’s continued development and growth,” I will design a high density housing complex in the Columbia City neighborhood of Seattle, WA. This development will include four, three-story buildings, natural landscaping, the introduction of urban forest patches, and a large community garden. The development will use sustainable construction methods, sustainable and locally sourced materials, passive design, water reuse, green energy, and merge into the surrounding landscape.

To be high-density, there will be 20 units per acre at about 1200 sq. ft. each. This will allow for site landscaping. The buildings will also include underground parking, workout facilities, and common space. The surrounding site will have an urban forest, natural landscaping, water features, community gardens, and walking paths.

Strategy

Natural landscape

Passive systems

Sustainable

Natural lighting

Natural cooling

Water management

Green energy

Integrate nature

Tactic

Rain gardens, plant local trees and plants

Optimal solar and wind orientation, super insulation, tight seal, shading, operable windows

Reuse or recycle construction waste/materials, construction methods avoid excess material waste (use standard lengths), low VOC materials

Large windows, skylights

Operable windows that align for cross breezes, shading

Collect rainwater for plant watering and grey water systems, rain gardens and ponds to manage storm water

Geothermal heating/cooling, wind turbine, solar panels

Every unit has private outdoor space, connects to common outdoor space, integrated green walls/green roof, passive heating/cooling systems

3D model built in Rhino, rendered in Kerkythea, edited in Photoshop.

3D model built in Rhino, rendered in Kerkythea, edited in Photoshop.

Presented on April 29, 2013.

3D model built in Rhino, rendered in Kerkythea, edited in Photoshop.